|

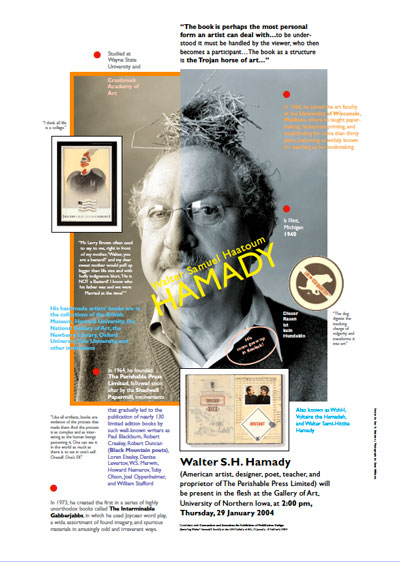

| Roy R. Behrens © Combat Fatigue. Digital montage (2004). |

When I initially made this digital montage—in a form that alludes to a book spread—it had nothing to do with the Irish novelist and poet James Joyce (1882-1941), at least not directly. In fact, the obscured image on the right is reworked from a photograph (in the Library of Congress) of an equally admired writer and Joyce's contemporary, the Irish poet and playwright William Butler Yeats (1865-1939). But it had everything to do with writing and designing. Years earlier, when I was in an architecture class in graduate school (the only one I've taken), I began to think about Venn diagrams in relation to figure-ground patterns, and then, by extension, to architectural building plans. In part I was led to this by the writings of Christopher Alexander. It seemed to me then that one can make purposeful "category confusions" (puns, rhymes, parodies, allusions and so on) in architectural building plans as easily as one can with words. I was "reading" Finnegans Wake at the time, so to some extent this came to me because of their concurrence.

Not to pretend to explain Joyce's comic novel, its two central characters are HCE (Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker) and ALP (Anna Livia Plurabelle). Beyond that, you can find a detailed and reasonably good summary at the Wikipedia article on the book. For the moment, I would simply like to share a few examples of the astonishing word play that Joyce employs throughout the book.

He frequently offers sentences that say one thing and yet, by the way they are written, they echo (or parody) other famous passages, especially religious texts. Listen to these two examples:

"In the name of Annah the Allmaziful, the Everliving, the Bringer of Plurabilities, haloed be her eve, her singitime sung, her rill be run, unhemmed as it is uneven!"

"Wharnow are alle her childer, say? In kingdome gone or power to come or gloria be to them farther? Allalivial, allaluvial! Some here, more no more, more again lost alla stranger."

The complexity of the patterns he makes is beyond belief. Here's a particularly interesting part in which he poses a question, then follows with an answer:

"8. And how war yore maggies?

Answer: They war loving, they love laughing, they laugh weeping, they weep smelling, they smell smiling, they smile hating, they hate thinking, they think feeling, they feel tempting, they tempt daring, they dare waiting, they wait taking, they take thanking, they thank seeking, as born for lorn in lore of love to live and wive by wile and rile by rule of ruse 'reathed rose and hose hol'd home, yeth cometh elope year, coach and four, Sweet Peck-at-my-Heart picks one man more."

Finally, I don't know how many people realize that, throughout this astonishing book, Joyce has embedded word sequences—words that begin with h, c and e—to allude of course to HCE (the protagonist). There are tons of them, but here a few:

"Howth Castle and Environs. he calmly extensolies. Hic cubat edilus. How Copenhagen ended. happinest childher everwere. Hush! Caution! Echoland! How charmingly exquisite! human, erring and condonable. heptagon crystal emprisoms. Heave, coves, emptybloddy! Hengler's Circus Entertainment. Heinz cans everywhere."