Patrick Brydone, A Tour through Sicily and Malta: in a series of letters to William Beckford, Esq., of Somerly in Suffolk, from P. Brydone, F.R.S., 1773. English Edition: New York: Evert Duyckink, 1813—

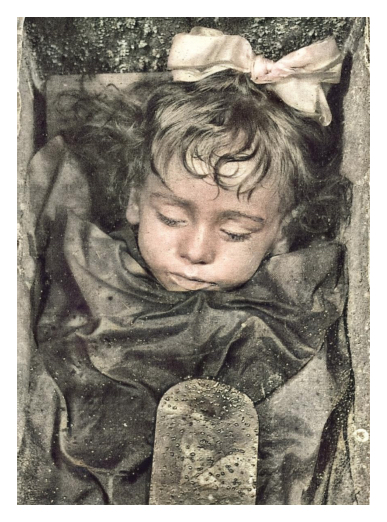

This morning we went to see a celebrated convent of Capuchins, about a mile without the city; it contains nothing very remarkable but the burial place, which indeed is a great curiosity. This is a vast subterraneous apartment, divided into large commodious galleries, the walls on each side of which are hollowed into a variety of niches, as if intended for a great collection of statues; these niches, instead of statues, are all filled with dead bodies, set upright upon their legs, and fixed by the back to the inside of the niche: their number is about three hundred: they are all dressed in the clothes they usually wore, and form a most respectable and venerable assembly. The skin and muscles, by a certain preparation, become as dry and hard as a piece of stock-fish; and although many of them have been here upwards of two hundred and fifty years, yet none are reduced to skeletons; the muscles, indeed, in some appear to be a good deal more shrunk than in others; probably because these persons had been more extenuated at the time of their death.

Here the people of Palermo pay daily visits to their deceased friends, and recall with pleasure and regret the scenes of their past life: here they familiarize themselves with their future state, and choose the company they would wish to keep in the other world. It is a common thing to make choice of their niche, and to try if their body fits it, that no alterations may be necessary after they are dead; and sometimes, by way of a voluntary penance, they accustom themselves to stand for hours in these niches…

Here the people of Palermo pay daily visits to their deceased friends, and recall with pleasure and regret the scenes of their past life: here they familiarize themselves with their future state, and choose the company they would wish to keep in the other world. It is a common thing to make choice of their niche, and to try if their body fits it, that no alterations may be necessary after they are dead; and sometimes, by way of a voluntary penance, they accustom themselves to stand for hours in these niches…

I am not sure if this is not a better method of disposing of the dead than ours. These visits must prove admirable lessons of humility; and I assure you, they are not such objects of horror as you would imagine: they are said, even for ages after death, to retain a strong likeness to what they were when alive; so that, as soon as you have conquered the first feeling excited by these venerable figures, you only consider this as a vast gallery of original portraits, drawn after the life, by the most just and unprejudiced hand. It must be owned that the colors are rather faded; and the pencil does not appear to have been the most flattering in the world; but no matter, it is the pencil of truth, and not of a mercenary, who only wants to please.