In a series of online talks on the history of design that I recently gave for Drake University's OLLI life-long education program, I spoke about the Bauhaus, which began in Germany in 1919. I discussed the influences of its teachers and students, some of whom emigrated to the US, where they joined existing schools or established their own. One of those schools was called Pond Farm, near Guerneville CA, where Marguerite Wildenhain worked with about twenty students each summer.

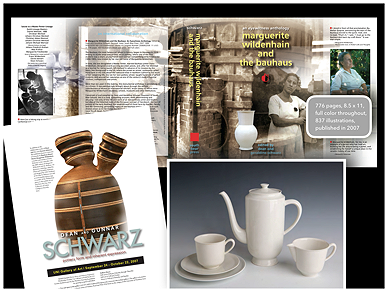

In a series of online talks on the history of design that I recently gave for Drake University's OLLI life-long education program, I spoke about the Bauhaus, which began in Germany in 1919. I discussed the influences of its teachers and students, some of whom emigrated to the US, where they joined existing schools or established their own. One of those schools was called Pond Farm, near Guerneville CA, where Marguerite Wildenhain worked with about twenty students each summer. Iowa potter Dean Schwarz and I were among her students in 1964. He returned in later years to be her assistant, and then established his own summer school, called South Bear School, near Decorah IA. He and his wife, writer Geraldine Schwarz, compiled and edited a huge, rich book about Wildenhain's life, titled Marguerite Wildenhain and the Bauhaus: An Eyewitness Anthology (South Bear Press, 2007), as shown in illustrations here.

|

| South Bear School, Decorah IA |