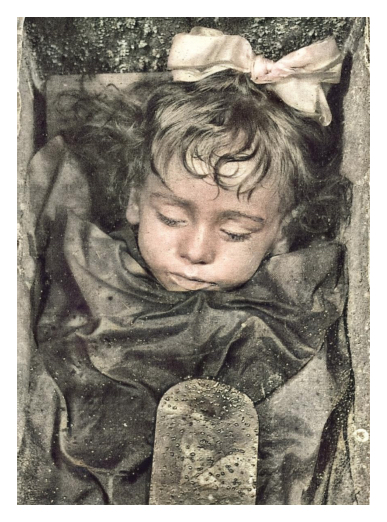

Above Roy R. Behrens,

Architectonic (© 2021). Digital montage.

•••

Wiliam Hazlitt, “On the Fear of Death” in Table Talk (1822)—

Perhaps the best cure for the fear of death is to reflect that life has a beginning as well as an end. There was a time when we were not: this gives us no concern—why then should it trouble us that a time will come when we shall cease to be?

•••

Roy R. Behrens, “Khaki to Khaki (Dust to Dust): The Ubiquity of Camouflage in Human Experience” in Ann Elias, et al., eds., Camouflage cultures: beyond the art of disappearance (Sydney AU: Sydney University Press, 2015)—

…“I am I” and, to follow, I am not “not-I.” Or, I am “self” as distinguished from “others.” We typically regard our “selves” as permeable identities in a bouillabaisse of ubiquitous “stuff,” a surrounding that seems to a newborn, in the famous words of William James, like “a blooming, buzzing confusion.” One wonders if this might also explain, as Ernst Schachtel suggested, why we are all afflicted by “childhood amnesia,” leaving us with little or no memory of the first years of our lives, because we lacked the “handles” then—the linguistic categories—that enable us to “grasp” events. In recent years, increased attention has been paid to the various forms of “amnesia” at the opposite end of life, including gradual memory loss, senility, dementia, and the horrifying ordeal of Alzheimer’s. If the boundaries of our figural “self” are blurred when we are newborns, perhaps we should not be surprised that the limits of our “self” grow thin—once again—as we totter toward the end of time.

As adults, we use hackneyed phrases like “dust to dust” to imply that at birth we somehow spring from naught; that we metamorphically evolve through infancy and childhood; live out our ritualistic lives as corporeal upright adults; then slowly—or, just as often, catastrophically—“deconstruct”; and (at last) are literally “disembodied” in the process that we dread as death. Instead of saying “dust to dust,” it may be more in tune to say “khaki to khaki,” since it seems as if our lives consist of time-based re-enactments of a spectrum of nuanced relations between figure and ground, some or all of which pertain to varieties of camouflage.

online access