Henry Miller, in Robert Snyder, This is Henry, Henry Miller from Brooklyn. Los Angeles: Nash Publishing, 1974—

Totoya Hokkei / Japanese Print

[When he was married but, as a writer, without an income] now and then my wife wasn't working maybe and, of course, I wasn’t selling anything—we’d have to separate, and I’d go home to live with my parents and she with her parents. That was frightful. When I’d go home to live with my parents my mother would say, “If anybody comes, a neighbor or one of our friends, y’know, hide that typewriter and you go in the closet, don’t let them know you’re here.” I used to stay in that closet sometimes over an hour, the camphor ball smell choking me to death, hidden among the clothes, hidden y’know, so that she wouldn’t have to tell her neighbors or relatives that her son is a writer. All her life she hated this, that I’m a writer. She wanted me to be a tailor and take over the tailor shop, y’know. It was a frightful thing—this is like a crime I'm committing. I’m a criminal, y’know. This standing in the closet… I'll never forget the smell of camphor, do y‘know. We used it plentifully.

Saturday, December 31, 2022

hide that typewriter and you go into the closet

Saturday, December 24, 2022

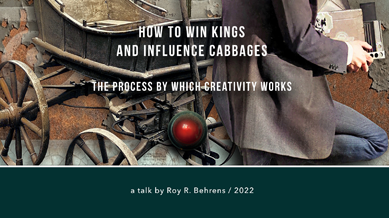

the process by which creativity works / video

mammoth flyer / elephantine mastodon hybrid

When I returned to the table, I found, to my surprise and great delight, that one of the students had spontaneously attached the airplane wings to the skeleton of the mastodon. I was so pleased by this invention that I permanently mounted the wings, added a wooden base, and painted the hybrid construction. Obviously, a new idea had taken flight, and the title I later chose for it was the Mammoth Flyer. It appealed to a wide range of people, as was confirmed, a few years later, when it was stolen from an art exhibition.

Saturday, December 10, 2022

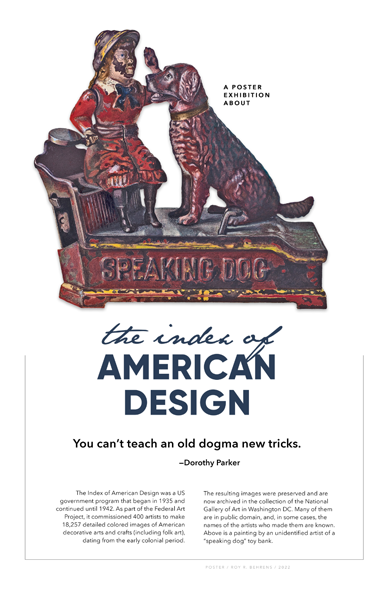

teaching dogs olde tricks all the way to the bank

Roy R. Behrens, poster from a series that pays tribute to the Index of American Design (1935-1942). The original watercolor painting is in public domain at the National Gallery of Art.

Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022)

when the evening is spread out against the sky

|

| Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022) with William H. Edwards image |

Shaker wisdom of restraint and understatement

Roy R. Behrens, poster from a series that pays tribute to the Index of American Design (1935-1942). The original watercolor painting is in public domain at the National Gallery of Art.

Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022) with Alois E. Urich image

Sancho Panza says Don Quixote off his rocker

Roy R. Behrens, poster from a series that pays tribute to the Index of American Design (1935-1942). The original watercolor painting is in public domain at the National Gallery of Art.

Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022) with John Davis image

feline gargoyle with fabulous embellishments

Roy R. Behrens, poster from a series that pays tribute to the Index of American Design (1935-1942). The original watercolor painting is in public domain at the National Gallery of Art.

Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022), with John Davis image

disarranged bandbox of a mad hatter's top hat

Roy R. Behrens, poster from a series that pays tribute to the Index of American Design (1935-1942). The original watercolor painting is in public domain at the National Gallery of Art.

Poster design © Roy R. Behrens (2022), with Gilbert Sackerman image

set off for India but arrive in America somehow

|

| Poster © Roy R, Behrens, with Ingrid Selmer Larsen image |

Ben Franklin's preference of turkey as symbol

Roy R. Behrens, poster from a series that pays tribute to the Index of American Design (1935-1942). The original watercolor painting is in public domain at the National Gallery of Art.

Poster design© Roy R. Behrens 2022

Tuesday, November 29, 2022

remarkable from the Index of American Design

|

| Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022) from Betty Fuerst image |

astonishing from the Index of American Design

|

| Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022), artist unknown |

a favorite from the Index of American Design

|

| Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022) with Mina Lowry image |

Monday, November 28, 2022

selection from the index of american design

|

| Poster © Roy R. Behrens (2022) with Mina Lowry image |

Sunday, November 27, 2022

exquisite image / the index of american design

Roy R. Behrens, poster from a series that pays tribute to the Index of American Design (1935-1942). This particular painting, by Daniel Marshack, documents a woman's gymnasium outfit. The original watercolor painting is in public domain at the National Gallery of Art.

Poster design © Roy R. Behrens (2022)

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Don Quixote / lunatics, lovers, and poets alike

Above William Lake Price, Don Quixote in his Study (Photograph, 1857), National Gallery of Art.

Don Quixote

•••

Roy R. Behrens, “Lunatics, Lovers, and Poets: On madness and creativity" in Journal of Creative Behavior Vol 8 No 4 (1975), pp 228ff—

Don Quixote has tunnel vision, by which he sees through the tunnel of love. Everything he sees relates to chivalry. It is as if he wore blinders, like Rocinante his “steed.”

He calls his neighbor a “squire.” He dons armored armour, with a cardboard visor top. He sees prostitutes as ladies. His unbridled imagination has left us with phantoms of windmills, whch are in turn synonymous with Quixote and quixotic. When he hears the “neighing of steeds, the sound of trumpets, and the rattling of drums,” his sidekick Sancho Panza sees “nothing but the bleating of sheep and lambs.”

Sancho Panza is conventional, while the knight-errant is errant. The “visionary gentleman” is either poetic or crazy. He confuses similarity with identity, whether by purpose or fault. A is not not-A, but inside Quixote’s mind, A and not-A merge as one. His five-and-dime descendant is the nearsighted cartoon character Mister Magoo, who (in Magoo Goes Shopping) sees and treats a rib cage (A) as if it were a xylophone (not-A), implying that musical pitch is related to the length of the ribs.…

In Magoo cartoons, Sancho Panza is Waldo. He is Watson in Sherlock Holmes. Sancho, Waldo and Watson represent unexceptional views. They know that A is A, that A is not not-A. “Look, sir,” Sancho calls out to the knight-errant, “those which appear yonder are not giants, but windmills; and what seem to be arms are sails…” more>>

•••

Below An interpretation of Don Quixote by José Guadalupe Posada, c1908.

Tuesday, November 22, 2022

Worm Runner's Digest meets the Unabomber

|

| Roy R. Behrens (1972) |

•••

How strange it is to run across an artwork, design, essay, or whatever, that dates from earlier in life, in this case fifty years ago. I can barely remember the brief time period during which I worked (remotely) with a then well-known (albeit controversial) scientist, a biologist and animal psychologist named James V. McConnell (1925-1990). In 1972, he was on the faculty at the University of Michigan, and had become “famous” for his claims of memory transfer in planeria, also known as “flat worms.” In 1962, he published a research paper in which he reported that when flatworms were conditioned to certain stimuli, and their body parts fed to other flatworms, the subsequent group appeared to learn more quickly. He concluded that this was evidence of a chemical transfer of memory, which he called Memory RNA. Eventually, other scientists failed to arrive at the same results as his experiments, and his findings were dismissed.

I think I became aware of McConnell, not just because of his flatworm research, but because he had founded an amusing double-purpose journal. One half of it was a serious scientific periodical called the Journal of Biological Psychology. The other half (printed topsy turvy to that, but bound with it, each bearing a separate cover) was a science humor journal, titled The Worm Runner’s Digest, in which he published satirical take-offs that looked like research papers, but were not.

Initially, when McConnell began this tandem periodical in 1959, the combined halves together were known as the Worm Runner’s Digest. But in 1966, he adopted two separate titles. On the JBP side of the journal, he published serious scientific articles such as his own research about “Memory transfer through cannibalism in planaria”; while, on the humorous WRD side, he published satirical articles, such as “A Stress Analysis of a Strapless Evening Gown.” Predictably, there were readers who objected, some of them claiming that it was sometimes too difficult to sort out the jokes from the science.

In 1972, I was a first-year university professor, just out of graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design, and had just begun to teach at the University of Northern Iowa. I don’t now recall how I became affiliated with McConnell and his journal. Surely I must have written to him, and I presumably sent him submissions, one of which he published in the JBP. It was a serious essay about anamorphic distortion in art in comparison to the diagrams in On Growth and Form by D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, the celebrated Scottish biologist. I also submitted a humorous collaged narrative (structured like pages of a comic book) that is not in the least bit funny now—but he kindly published it nevertheless in the WRD.

Our collaboration went on from there. In the early 1970s, McConnell published several of my illustrations as covers (my favorites are the two pen-and-ink drawings shown here). I also submitted a series of single-image comic collages (none of which are amusing today). These were heavily influenced by the collage-illustrated short stories of Donald Barthelme (who I had learned about in graduate school), using bits and pieces of antique steel engravings.

McConnell was in Michigan and I was in Iowa. We never met in person, and I don’t think we even spoke on the phone. But we did exchange letters, and his—if I’m not mistaken—were a lot longer than mine. I still have them somewhere. In the mid-70s, I moved to Wisconsin, and our exchanges slowed, then totally stopped.

There is a bizarre ending to this, which I did not learn about until a few years ago. In 1985, James McConnell was one of the people who were targeted by the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski. A package (which appeared to be a manuscript) was mailed to his house, where it was opened by a research assistant. When the bomb exploded, McConnell was in the same room. He escaped life-threatening injury, but he ended up with a substantial hearing loss. He retired three years later, and died in 1990.

|

| Roy R. Behrens (1972) |

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

Willi Baumeister cartoon / Hitler in electric chair

|

| Schlemmer (left) and Baumeister |

Willi Baumeister, in Hellmut Lehmann-Haupt, Art under a dictatorship. New York: Octagon Books, 1973, page 87—

My friends in Wuppertal, Oskar Schlemmer among them, sent me humorous letters and postcards from time to time, with paste-up pictures and surrealist texts. I sent them, rather naively, a cartoon, cut from a US newspaper, of an electric chair with Hitler on it. Suddenly I was summoned to Gestapo Headquarters. I was confronted by the Gestapo censor with my entire correspondence for the last year and a half. Thank God, Hitler in the electric chair was not among the intercepted letters. I extricated myself by writing a long report to the Gestapo, explaining that these were plans for a book dealing with color modulation and patina, in connection with an especially resistant paint for the camouflaging of tanks and pill boxes.

Tuesday, November 15, 2022

today I bought a dress that is made out of wood

Ione Robinson, A Wall to Paint On. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1946, p. 373-374, while visiting Berlin, from a letter dated November 8, 1938 (less than a year in advance of the start of World War II) —

Where is the fifth pig?

Today I bought a dress that is made out of wood. I still can't believe it. In fact, there was not one “natural” item in this department store; everything was synthetic. In an arcade on Unter den Linden, I spent a long time looking at photographs of Hitler and I bought a series of tiny "flap” [flip book] photos which, when you riffle them fast, make him come to life like a miniature movie. The one I have shows him making a speech and if you riffle the pages slowly the gestures are so calculated and ridiculous they make you laugh—although that is one thing I have not seen people do in this city.

The people in the streets [of Berlin] look worn and tired. Life is completely regulated. There are signs every few feet, telling one what to eat and believe. Money is controlled. Four dollars a day is about all you can spend. In a certain sense, this makes life very simple—you know exactly what you can and cannot do. Even though certain things could be achieved through such a system, I don't see how anyone could be happy. I begin to feel as though I were living in a well-run jail. There is the same security of a bed at night, something to eat, and a few hours of “forced” recreation. But the realization that one must constantly yield to the will of a single man takes all the incentive and moral force from a human being.

Sunday, November 13, 2022

always in the throes of a long drinking bout

|

| photograph of Amedeo Modigliani |

PARIS, Feb. 6—H. Hodglieni [sic] [Amedeo Modigliani], an artist, who claimed to have invented cubist painting, was found dead in a hovel in the Latin Quarter. He used to frequent Paris cafés dressed in trousers with legs of different colored materials.

•••

Ilya Ehrenburg, People and Life: memoirs of 1891-1917. London: MacGibbon and Kee, 1961, p.143—

…no one now can give an exact description of how [artist Amedeo] Modigliani used to dress: when times were good he wore a coat of light velvet with a red silk scarf round his neck, but when he was in the throes of a long drinking bout, ill and penniless, he was enveloped in brightly colored rags.

Tuesday, November 8, 2022

Armitage as impressario and aristocrat of art

Above I have written about the American graphic designer Merle Armitage because he was, undoubtedly, an accomplished book designer, whose primary income came from his activities as a "booking agent" or "impressario" for prominent performing artists, among them Anna Pavlova, Amelita Galli-Curci, Rosa Ponselle, and the Diaghilev Ballet. He wrote books about these and other artists because, as he once explained to Henry Miller, it provided him with the opportunity to design books, which is what he most enjoyed. My long essay on his life is online here. At the same time, I have also known that some of his personal qualities were less than admirable. I was reminded of that as I recently read this passage in Ione Robinson's autobiography (below).

•••

Ione Robinson, A Wall to Paint On. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1946, page 79—

The heat is stifling, and I have spent most of the day sitting [in Los Angeles] in the Plaza waiting to meet the Mexican Consul. I tried to forget the heat by reading something Merle Armitage gave me as I was leaving: a copy of his address before the California Art Club's Open Forum. It didn't help me bear the heat; in fact, it really frightened me, because Mr. Armitage seems to want to be the Lorenzo de Medici of Los Angeles. Already everyone listens to him, and the younger artists at home are under his thumb, simply because he can afford to buy a canvas when he wants to (although he never spends over a certain amount on any canvas, which is so small that in the end it does not really help a poor painter). But in this speech he is trying to prove that there is an “aristocracy in art”: he carefully quotes Webster on the definition of Aristocrat and Common, and then tries to twist a special meaning out of these words that will justify his right to judge esthetics. I really believe that he would like to feel that he is the arbiter of greatness in the art of our time. He believes that the masses of people have nothing to contribute to art, nor is their judgment to be relied upon, and argues that without people like himself there would never have been artists and writers like El Greco and Voltaire. What he forgets is that El Greco and Voltaire painted and wrote for the people, and not just for men like Merle Armitage. He actually wrote this: “How can the really common people have anything in common with, anything of sympathy for, as aloof and aristocratic a thing as art? If left to the common people, and I use the word ‘common’ as I have previously defined it, there would be no art.” The reason this frightens me is because Mr. Armitage is already the manager of the Los Angeles Grand Opera Association, and now seems on the verge of being the impresario of painters in California. I am glad I'm going to Mexico.

|

| Ione Robinson (source) |

Saturday, November 5, 2022

tobacco road / the story of a boy who smoked

EVOLUTION OF A BOY WHO SMOKED, in The Journal (Huntsville AL), February 28, 1907, p. 2. Reprinted from the Chicago Daily News. Artist unidentified—

Do you know any little boy that [sic] smokes cigarettes? If you do, just show him this picture. It is the sad story of Dick Sillypate. He saw another boy smoking a cigarette, and thought it looked so manly that he would try it himself. The picture shows what happened to him at the end of five months.

Friday, October 28, 2022

having a whale of a time on Nantucket Island

J. Hector St John de Crevecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer. UK: Davies and Davis, 1782—

A singular custom prevails here [on Nantucket Island] among the women, at which I was greatly surprised, and am really at a loss to account for the original cause that has introduced in this primitive society so remarkable a fashion, or so extraordinary a want. They have adopted these many years the Asiastic custom of taking a dose of opium every morning; and so deeply rooted is it, that they would be at a loss how to live without this indulgence; they would rather be derprived of any necessary than forego their favorite luxury. This is much more prevailing among the women than the men…though the sheriff…has for many years submitted to this custom. He takes three grains of it every day after breakfast, without the effects of which, he often told me, he was not able to transact any business.

Saturday, October 8, 2022

the man who made distorted rooms / a trilogy

Wednesday, September 28, 2022

El Lissitzky Loren Eiseley and S. Howard Bartley

Above I find this amazing. A composite multiple-exposure photograph by El Lissitzky, The Studio.

•••

S. Howard Bartley [his autobiography], A Bit of Human Transparency. Bryn Mawr PA: Dorrance, 1988—

…This is about a little boy who had no brother or sisters and only occasional playmates. He lived in a world of imagination. Imagination filled his life and he didn't learn much about people. It was his Aunt Clara and his grandmother who mainly made up the human circle for him. His mother had died when he was three weeks old. Although his father was part of the family, he didn't count. Later his [father's] stern discipline left its mark. So this story is also about the boy reaching manhood and a career as scientist and teacher, and about his impressions and outlook on life.

This boy was me, and from here on I'll tell my own story.

…

Another person who has enriched my life is Loren Eiseley, the noted anthropologist. First of all he reached me because he, like me, was a loner as a little boy. His description of his childhood [in All the Strange Hours] is one of the most fascinating and touching modern tales I ever read. It, with his career, is an example of what can develop when a child is left alone enough to think and wonder—as in constrast to what happens when a child jostles elbows all day long wth other children. From this comes politicians and the opposite of scholars.

Friday, September 23, 2022

film trilogy on artist / scientist Adelbert Ames II

|

| Colleagues Gary Gnade and John Volker in an Ames Room |

I began to research and to write about Ames in the late 1960s, and, in the many years since, I’ve continued to collect a fairly substantial amount of material related to him, including unpublished correspondence. I have always hoped to write a book about his life and ideas, but it was delayed by various circumstances, and now, as I age—and books become less useful as ways to share ideas—that project is on the back burner. So I have turned instead to making a series of video talks. Not the same thing, obviously, but it will do for the moment.

The first video in the series, titled Ames and Anamorphosis: THE MAN WHO DISTORTED ROOMS / Part One, was completed earlier this month, and is accessible online. It provides an overview of Ames’ life and his accomplishments, as well as information about his interesting family (he was related to writer / editor George Plimpton).

|

| Ames and Anamorphosis / Part One |

Part Two is all but finished, and should be available on the same channel in a matter of days. It documents the use of anamorphic distortion (forced perspective) in the history of art and in the research of vision. Although the Ames Demonstrations were highly unusual when they gained popularity in the 1940s, the optical principles on which they were based had been anticipated by Leonardo da Vinci, Hans Holbein, various Dutch artists, and, in science, by Hermann von Helmholtz.

Part Three will consist of an overview of the connections between the Ames Demonstrations, and various artistic and scientific achievements that took place during and after his lifetime, such as avant garde filmmaking, perspective distortion in ship camouflage, Hoyt Sherman's vision laboratory at Ohio State University, comedian Ernie Kovacs, theatrical special effects, the reverspective artworks of British artist Patrick Hughes, and so on.

In the early 1970s, I reconstructed several of the Ames Demonstrations, and, collaborating with a friend and colleague, John Volker, I designed a multi-faceted hands-on exhibition, in which children could experience a full-sized distorted room, a straight-forward forced perspective room, an upsidedown room, and so on. Over the years, I went on to publish articles about various aspects of his work in research journals, the online links to some of which are listed below.

•••

Behrens, R. R. (1987). The Life and Unusual Ideas of Adelbert Ames Jr. Leonardo: Journal of the International Society of Arts, Sciences and Technology, 20, 273–279.

Behrens, R. R. (1994). Adelbert Ames and the Cockeyed Room. Print magazine, 48:2, 92–97.

Behrens, R. R. (1997). Eyed Awry: The Ingenuity of Del Ames. North American Review, 282:2, 26–33.

Behrens, R. R. (1998). The Artistic and Scientific Collaboration of Blanche Ames Ames and Adelbert Ames II. Leonardo, 31, 47–54.

Behrens, R. R. (1999). Adelbert Ames, Fritz Heider, and the Chair Demonstration. Gestalt Theory, 21, 184–190.

Saturday, September 10, 2022

a remote radio drawing course taught in 1932

There is a legend, true or not, that Hungarian-born Bauhaus designer and photographer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy once created an artwork over the phone. Henceforth, as Rainer K. Wick said in Teaching at the Bauhaus (Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2000), it might be the conclusion of some that “art in the industrial age could consist of an anonymous machine process of high precision and exist independently of the personal intervention of the artist’s hand; thus the act of artistic creation should be seen in the intellectual aspect and not in the manual one.”

Moholy’s experiment comes to mind whenever I see this vintage magazine article on so-called “Radio Comics” [shown above], as published in an issue of Popular Mechanics in 1932. The instructor is a radio broadcaster, who makes a drawing on a grid-based page, consisting of 144 numbered squares. His pupils, who are listening remotely to the broadcast, have been given an indentical page of numbered squares—but without a drawing.

“As the instructor draws a figure, he calls out the squares touched by his pencil or crayon. Pupils sitting at the radio with duplicate charts trace lines from one number of another as they are announced in efforts to ‘copy’ the work of the instructor.”

Actually, the only thing innovative about this (at the time) was the use of the radio. The practice of “squaring off” a drawing (called mise au careau) in order to copy, enlarge or reduce the image onto a second squared-off surface, was practiced as early as the Ancient Egyptians. Here is an example of that by the artist Sassoferrato.Later artists (among them Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, and Vincent Van Gogh) not only relied on that same approach, but also used “drawing frames” (of which Dürer's and Van Gogh's are shown below) by which they looked at the model through a network of suspended threads, arranged to match a pattern of squares on their drawing paper. Leonardo highly recommended this—

“If you wish to learn correct and good positions for your figures [he wrote], make a frame that is divided into squares by threads and put it between your eyes and the nude you are drawing, and you will trace the same squares lightly onto your paper on which you intend to draw your nude.”

After the invention of photography, artists began to square off photographs of their models, as a gridwork guide for drawing. Still other artists (among them Blanche Ames Ames and Adelbert Ames II) make efficient use of large-scale grid-based frames which the model stood behind as the photograph was made. Below is a photograph of that in her Borderland studio.

Tuesday, July 19, 2022

Sunday, July 10, 2022

beak of the pelican holds more than his belican

|

| more>>> |

Oh, a wondrous bird is the pelican!

His beak holds more than his belican.

He takes in his beak

Food enough for a week.

But I'll be darned if I know how the helican.

Thursday, July 7, 2022

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

a retrospective reverie on 46 years of teaching

Each presentation was limited to fourteen minutes. Having retired at the end of 2018, after having taught graphic design illustration and design history at various art schools and universities for more than 45 years, my presentation consisted of an 8-minute retrospective reverie on my memories of working with students, titled Solving Problems in Design. This was presented as a video, and can now be viewed online.

Sunday, June 26, 2022

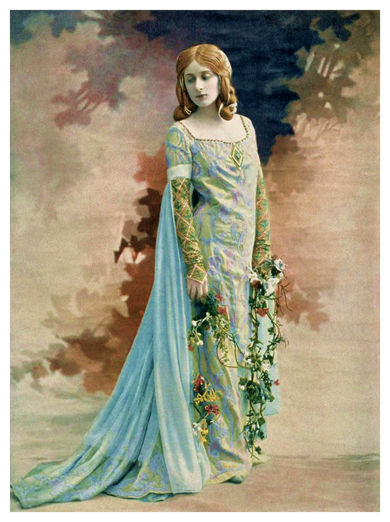

improvisation on stage / unrehearsed adjustment

|

| Mary Garden |

We were thrilled [having been given tickets to attend a performance of Le Jongleur, an opera starring the famous soprano Mary Garden]…we had never seen it, longed to do so, had not been able to afford seats. The performance outstripped even our expectation; Mary Garden was an exceptionally skilled actress as well as an exceptionally fine singer. She was also a first-rate “trooper.” The market scene came to an end; the stage was being cleared for her entrance, the crowd dispersing; suddenly in the very center of the stage a donkey refused to budge, straddled his legs and performed an act which had been rehearsed. The audience grasped, then rocked with laughter; the donkey, satisfied, made an effective exit. Mary Garden entered upstage center, seemed not even to glance at the spot where she would otherwise have stood, crossed down a little to the left of it and began to sing. In one second there was not a sound from that crowded house.

Saturday, June 25, 2022

a report of naiveté in assessing works of art

Abel Warshawsky, The memories of an American Impressionist. Kent OH: Kent State University Press, 1980, p. 62—

Cavern [detail] © Roy R. Behrens 2021

[In Paris] The "cult of the naive" at all costs became a rage…

A group of painters in Montmartre decided to exploit this hysteria and have some fun with the critics. Procuring a donkey, they tied a large paintbrush to his tail, first dipping the brush into an assortment of colors. Then a canvas was set up within striking distance of the donkey's tail, which in its gyrations soon covered the canvas with a weird conglomeration of colors—quite a stunning study in the new style, as the spectators all agreed. Witnesses and a notary, who had been invited to attend, attested to the manner in which the work had been done. This canvas was framed and sent to the Salon des Independants. It bore as title, if I remember rightly, Sunset on the Red Sea. After several well-known critics had remarked it and written about it as a work of extraordinary interest, the story with the signatures of the witnesses was published, and the laugh was on the "new art" critics.

Also see Art by Animals video, Desmond Morris, and pandemic montages.

Friday, June 24, 2022

adrift in milan / never too late for the last supper

Abel Warshawsky, The memories of an American Impressionist. Kent OH: Kent State University Press, 1980, pp. 86-87—

Wind Instrument [detail] © Roy R. Behrens

In connection with the Last Supper, a friend of mine, Samuel Cahan, a well-known newspaper artist who had been with the New York World for thirty years, told me of an amusing incident which occured when he and his wife visited Milan a few years ago. Speaking no Italian, they had asked their hotel porter to procure an English-speaking cabby to take them about. To the latter my friend very carefully explained that they wished to see the Last Supper. "Last supper?" replied the cabby, "yes , yes. Me understand!" Whereupon he started driving them round the town and finally into the country.

After the drive had extended for several miles, my friend, fearing that there must be some mistake, repeated his instructions to the driver. "Last supper?" he yelled back, "Sure! Me understand!" and continued to drive. Late that evening the two Americans were finally brought back to the city in a state approaching nervous exhaustion. Drawing up his carriage in front of a brilliantly lit edifice, the vetturino opened the cab and ushered his fares into a fashionable restaurant, proudly giving them to understand that he had brought them back in good time for the desired "late supper."

Thursday, June 23, 2022

democratic privilege and the queen's bladder

Above © Roy R. Behrens, Revisiting Thomas Eakins [detail], 2021.

•••

Muriel Spark, Momento Mori. New York: Penguin Books, 1961—

The real rise of democracy in the British Isles occurred in Scotland by means of Queen Victoria’s bladder…When she went to stay at Balmoral in her latter years a number of privies were caused to be built at the backs of little cottages, which had not previously possessed privies. This was to enable the Queen to go on her morning drive round the countryside in comfort, and to descend from her carriage from time to time, ostensibly to visit the humble cottagers in their dwellings. Eventually, word went round that Queen Victoria was exceedingly democratic. Of course it was due to her little weakness. But everyone copied the Queen and the idea spread, and now you see we have a great democracy.

Thursday, June 16, 2022

online course on the history of design / 2022

Above This is a brief film overview of a four-week course I will be teaching (online), beginning in the first week in October, titled A History of Design: Graphic, Industrial, and Architectural Design in Europe and the US Since 1850. This is Part Two of a series of four. It is one of the fall semester offerings through OLLI at Drake (Oster Lifelong Learning Institute at Drake University). Registration will open during August at <https://alumni.drake.edu/olli>.

Course Introduction Video

Monday, June 13, 2022

Coming Soon / Graphic Design Symposium

The concluding highlight of the exhibition will be a two-day symposium, to be held on June 23 and 24, in the Art Loft Conference Room, Art Lofts Building, in the Department of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison at 111 North Frances Street, in Madison. Some participants are attending in-person, while others (worldwide) are registering online for free tickets, and, since it is a hybrid event, they will participate online as speakers, panelists and observers.

Please note, although participation is free, you must register at this link in advance.

|

| Iowa Insect Series (stages animated) |

Included in the exhibition is a series of ten large-scale digital montages, called the Iowa Insect Series, that were made in 2012-2013 in collaboration with design colleague and friend David M. Versluis. At the time, he was a Professor of Art and Design at Dordt College in Iowa, while I was then on the faculty at the University of Northern Iowa in Cedar Falls.

Also on exhibit are thirteen design-related images that are part of my long-term, continuing research (as a design historian) of World War I Allied naval camouflage. The theme uniting these artifacts is high difference or disruptive ship camouflage, which was referred to at the time as dazzle painting or dazzle camouflage. Among the items exhibited are restored government photographs from the time period, full-color reproductions of diagrams of the camouflage patterns, and my own recent hypothetical camouflage schemes, derived from historical works of art.

|

| Iowa Insect Series |