|

Guggenheim Museum under construction

|

The famous bungled robbery of the First National Bank in

Northfield MN took place on September 7, 1876. The outlaw gang was headed by

Jesse James and

Cole Younger, who, as ardent Southerners, were infused with anger about the recent Civil War.

They were especially resentful toward Union General Adelbert Ames (Reconstruction Governor of Mississippi), and his father-in-law, General Benjamin F. Butler (both greatly hated in the South). In postwar years, the James and Younger gang had learned that ex-Governor Ames had moved north to Minnesota, where he (and General Butler) had invested in a flour mill on the Cannon River, and were on the board of directors at the Northfield bank.

Nearly one hundred years later, in 1972, the Northfield Historical Society produced a publication about the city’s history, titled Nuggets from Rice County Southern Minnesota History, which featured articles about the bank robbery as well as the role the Ames family in the development of the town. That publication was edited by a Northfield architect and local historian named Robert Roy (Bob) Warn (1924-1977), who had been a student of Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesen, near Spring Green WI, in the late 1940s or early 1950s.

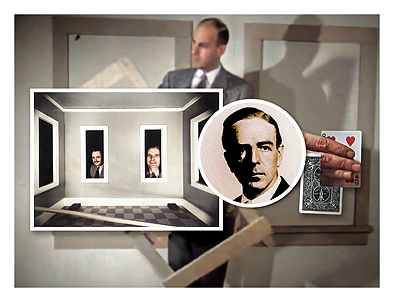

In that publication, Warn briefly mentions that a son of General Ames was Adelbert Ames Jr. (aka Adelbert Ames II) (1880-1955). Initially trained as a lawyer, the younger Ames switched professions from law to art, to psychology and optics. During the 1940s, he became especially known for having devised about twenty illusion-based laboratory set-ups called the Ames Demonstrations in Perception, notably the Ames Distorted Room and the Rotating Trapezoid Window.

|

laboratory-sized Ames Room

|

In March 1947, as part of its bicentennial,

Princeton University hosted a three-day conference on “Planning Man’s Physical Environment.” Invited as participants were seventy prominent speakers, among them leading architects, philosophers, and social psychologists [see photo below]. Adelbert (Del) Ames Jr. (of whom most were probably unaware) was among those featured, as was the famous (and typically outspoken) Frank Lloyd Wright, who gave a controversial speech. The two men met, during which Wright spoke admiringly of the Ames Demonstrations, which had been on exhibit at Princeton for three months.

|

Ames (5 from left) and Wright (2 from right), front row

|

Following the conference, Wright recommended Ames’ demonstrations to others, including

George Nelson, the well-known industrial designer. In a letter to artist / educator

Hoyt Sherman at Ohio State University, Ames wrote that “I had the most interesting and stimulating time at Princeton. Practically all the attending members went through the demonstrations and got a great kick out of them, and all wanted copies of any literature that we had on the matter.”

Back at Wright’s Wisconsin studio-school (as recalled by Northfield historian Warn), the architect “told us, his apprentices, of his meeting with Ames at Princeton University…and how the SR Guggenheim Museum, then being designed, was to be an institute for the celebration of the eye—an optical museum.”

It was Wright’s idea that the Ames Demonstrations should be a permanent part of the

Guggenheim Museum, but that decision could only be made by

Baroness Hilla von Rebay, who was the museum’s co-founder and first director.

Solomon Guggenheim was 88 years old (he died the following year), and the baroness (as Ames documents attest) was “in full control of his art expenditures.” As one of Ames’ associates (John Pearson) noted in a memo after the Princeton event, “She [the baroness] is one of the strangest persons in the world, a psychopathic case, a mystic, a very troublesome person, a hero worshiper.” Whatever Wright’s ambitions, the best that he could hope for was a meeting between Ames, Rebay, and himself. But that meeting never took place. Later, a separate proposal was made (without Wright’s involvement) to exhibit the Ames Demonstrations at the

Museum of Modern Art, by appealing to

Rene d’Harnoncourt, the museum’s director, but that too did not come about.

•••

As a young graphic design teacher (c1970) who believed that art, design, and architecture should be informed by vision, I replicated some of the Ames Demonstrations for use in exhibits and classroom teaching, and began to publish articles on such subjects as

Gestalt theory,

anamorphosis,

stereo vision, and

camouflage. Over the years, my interest in Ames has continued intermittently. I visited Northfield, spoke at Dartmouth, and corresponded now and then with his associates and relatives (among his nephews was the writer

George Plimpton). I also published articles on his demonstrations, his early collaboration with his sister (artist and suffragist

Blanche Ames Ames), and the indebtedness of his work to anamorphic distortion in art, to

disruptively-patterned ship camouflage (called “dazzle camouflage”), to aspects of Gestalt theory, and to the early experiments in cinema by

Dudley Murphy (who worked as Ames’ laboratory assistant),

Fernand Leger,

Man Ray, and others.

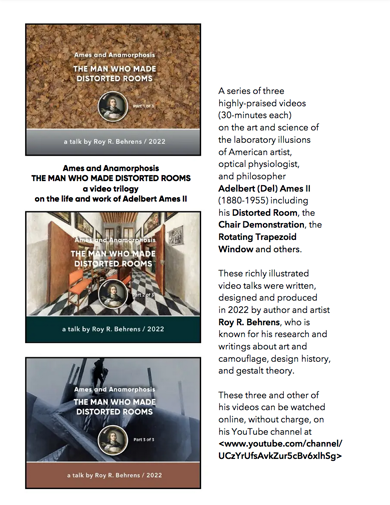

In 2022, having strayed into producing online documentary talks, I made a three-part series of films (30 minutes each) about Ames’ life and influence, titled

Ames and Anamorphosis: THE MAN WHO MADE DISTORTED ROOMS. These are accessible online, and free to share with others.

•••

Since the 1930s (almost a century has passed), interest in Del Ames and his demonstrations has risen and fallen, time after time, as society’s concerns have changed. At Harvard, Ames had studied with

William James. Eventually, he became associated with

Transactionalism, a spin-off of

Pragmatism (inspired by

John Dewey), in which it was asserted that human experience is not direct objective witnessing, but consists of an amalgam of sensory input, past experience, desires and expectations.

Del Ames may be due for revival again, if (to quote

Peter Godfrey-Smith in the June 2024 issue of

The New York Review of Books) “we have nothing like the simple, direct contact with the world around us that we suppose. Instead…our brains actively synthesize a picture of the world, continually guessing, extrapolating, and projecting.” And while our sensory input may constrain what we experience, “the constraint can be tenuous, and ordinary perception may be akin to a ‘controlled hallucination’…”

As Ames himself once put it: “The things we see are the mind’s best bet as to what is out front.”