Grandin is world-famous, and I have long been interested in her work. Few people are as widely admired. Since 1984, she has been the recipient of 101 prestigious awards, including honorary doctorates from the leading universities, being chosen for Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People, inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Science, and named as one of the Top Best College Professors in the US.

That’s phenomenal. Given all that she’s achieved, how could she possibly even attend all those award ceremonies, and still remain productive? She is one year younger than I am. I cannot begin to imagine receiving so many awards—I would never have accomplished anything. Maybe I am fortunate that the less-than-prestigous awards I've received can be counted on one hand. And I don’t have extra digits.

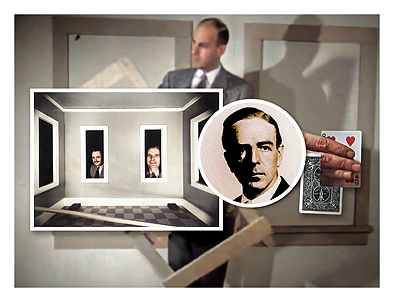

My interest in Grandin reached its peak in 2010, with the release of a popular Hollywood film about her life, in which she was portrayed by actress Clare Danes. At the beginning of the film, we learn about a turn of events that occured while she was in high school. She saw an educational film about the then popular laboratory experiments of American artist and optical physiologist Adelbert (Del) Ames, Jr., usually referred to as the Ames Demonstrations. The best-known of these are the Ames Window (in which a rotating window-like cut-out appears not to rotate, but to sway back and forth), and the Ames Distorted Room (in which people’s sizes appear to change as they move around a cleverly misshapen room interior).

Since Grandin and I are nearly the same age, we were probably introduced to the Ames Demonstrations at around the same time. Her response was to try to figure out how to build an Ames Room. She succeeded. As an aspiring art student, with a familarity with perpective and anamorphosis, I too replicated an Ames Room, an Ames Window, and other demonstrations, then spent a substantial amount of my life researching and writing about his development as an artist. And indeed, today I continue to publish new findings.

Over the years, I published multiple articles on the Ames Demonstrations and their significance. In the text and bibliography of her book, Grandin refers to one of my articles, published in 1987, titled “The Life and Unusual Ideas of Adelbert Ames, Jr.” In the text, she even mentions me by name, for which I am grateful, because it is far more common for other authors to make blatant use of another author’s research, but neglect to credit it as a source.

In this case, there is a peripheral downside. While I have been credited, it was disappointing to find that I was also wrongly quoted. In my article, I had quoted a published statement by prominent Harvard psychologist Jerome Bruner, who had been married to Ames’s niece. Bruner and his wife’s uncle apparently had their quibbles, and, in his autobiography (1983), Bruner discounted the impact of Ames’s research with the following statement: “It was demonstration that he [Ames] was after, not experimental manipulation. And demonstration of a kind that, I think, speaks more to the artist’s wonder than to the scientist’s. In the end, he had little impact on psychology or philosophy, but he continues to facinate artists.”

In Grandin’s book, she doesn’t mention Bruner. She states instead that it was “Roy R. Behrens, Professor of Art at the University of Northern Iowa” who “concludes that much of Ames’s work has more appeal for the artist than for the scientist. As a visual thinker, I have to disagree.” But I myself did not disparage Ames’s work. I only quoted Bruner, as one view of a prominent scientist, which, in the original article, I then qualified with a lengthy footnote on writings by others who may or may not have agreed with Bruner’s dismissive assessment.

In the end it doesn’t especially matter of course. I continue to be greatly pleased to have been mentioned by someone whose achievements are exemplary, and whose work is so well known.

•••

NOTES

Temple Grandin has also written about her interest in the Ames Demonstrations in Temple Grandin and Margaret M. Scariano, Emergence: Labeled Autistic, New York: Warner Books, 1996.

More recently, I have produced a series of three online video talks (30 minutes each) which provide an overview of Del Ames, his life and his accomplishments. These to some extent are based on my published research articles, but they also include new, surprising information that I have found more recently. These can be accessed free online at <https://youtu.be/MAEjgatMkio>, <https://youtu.be/-8gaYm2FUI0>, and <https://youtu.be/mxOEx2JLQBA>. My articles on Ames include:

Roy R. Behrens, “The Life and Unusual Ideas of Adelbert Ames, Jr,” in Leonardo, vol 20 no 3 (1987), pp. 273-279.

______________, “Adelbert Ames and the Cockeyed Room,” in Print magazine, vol 48 no 2 (1994), pp. 92–97.

______________, “Eyed Awry: The Ingenuity of Del Ames,” in North American Review, vol 282 no 2 (1997), pp. 26-33.

______________, “The Artistic and Scientific Collaboration of Blanche Ames Ames and Adelbert Ames II,” in Leonardo, vol 31 (1998), pp. 47-54.

______________, “Adelbert Ames, Fritz Heider, and the Chair Demonstration,” in Gestalt Theory, vol 21 (1999),” pp. 184–190.

I have also provided Ames biographical articles for Encyclopedia of Perception, Grove Online Dictionary of Art, askArt, and Allgemeines Kunstlerlexikon.